Sir Lawful Stupid and the Chaotic Murder Hobos

Challenging the 9 Alignments of Dungeons and Dragons

It’s storytime, friends! It’s a tale of Good and Evil, of True Neutrality and the constant battle between Law and Chaos.

I’m speaking of course of the Dungeons and Dragons alignment chart, which has been absolutely memed to death in images like these:

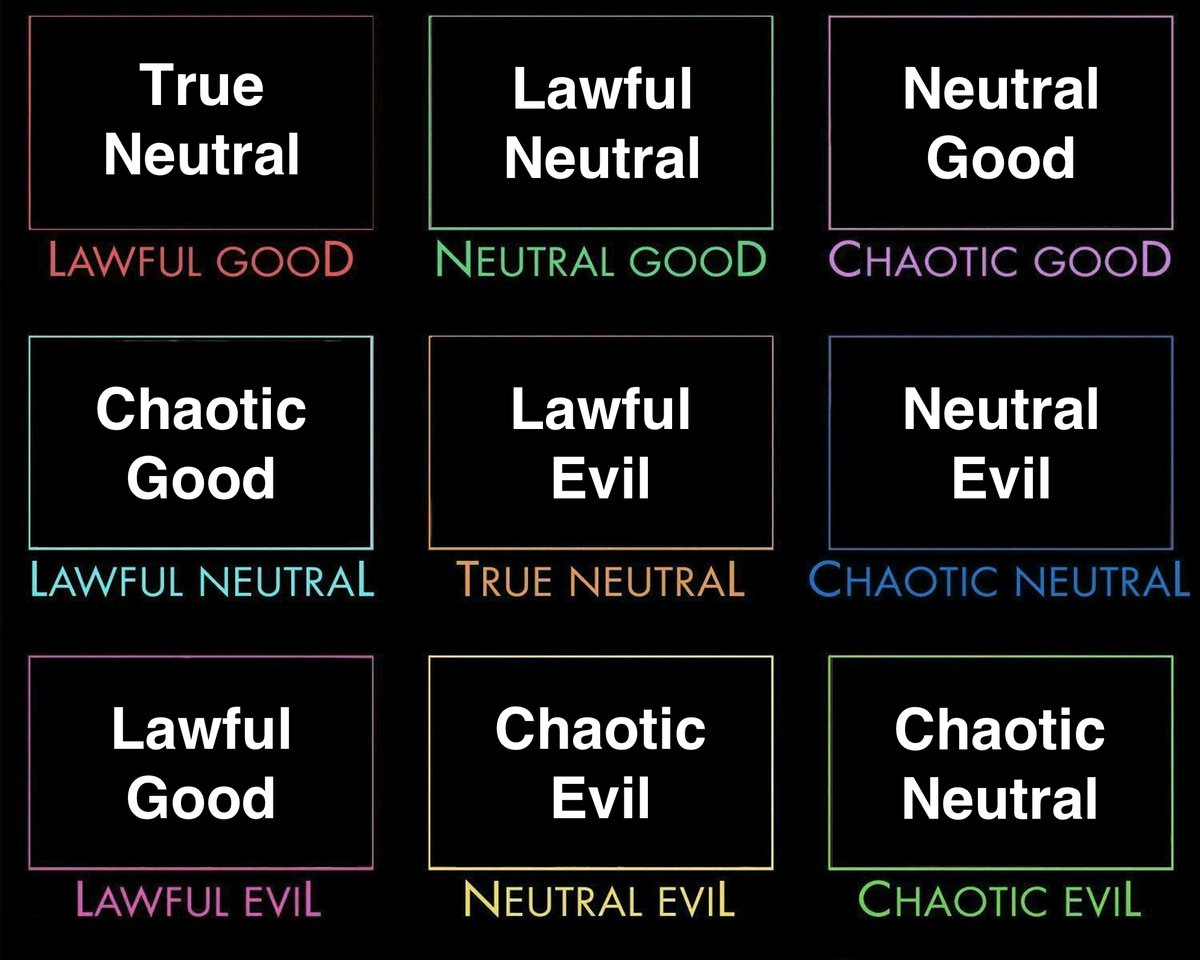

Anyone casually familiar with tabletop roleplaying is probably aware of the 3x3 alignment grid, so I will keep this explanation brief.

Dungeons and Dragons has historically had two alignment axes.

Good → Evil

and

Lawful → Chaotic

These function to neatly categorize a character’s morality into one of nine little boxes, as above. Personally, as a Canadian, I think the cobra chicken is chaotic evil, not neutral evil, but I digress.

The orginal Dungeons & Dragons, circa 1974, only had one axis: Lawful→Neutral→Chaotic.

All characters and monsters ticked one of these three boxes.

In 1979, Advanced Dungeons & Dragons added Good → Neutral → Evil. These twin axes combined to produce the nine alignment options that have become culturally ingrained in popular roleplaying systems.

In many ways, D&D treated alignment as a linear moral progression from best (lawful good) to worst (chaotic evil).

Lawful Good (aka best good boy) → Neutral Good → Chaotic Good → Lawful Neutral → True Neutral (unaligned, think Switzerland) → Chaotic Neutral → Lawful Evil → Neutral Evil → Chaotic Evil (aka worst bad boy)

This moral progression is where the problems with the alignment system begin.

Unless you had a particularly vindictive DM, persistent changes in behaviour could only change a character’s alignment by one step up or down. For example, a Lawful Good character who didn’t follow the laws could “fall” a step down to Neutral Good.

Or a Neutral Evil character who… got better, I guess, could become Lawful Evil. A character couldn’t have a ‘come to Jesus’ moment, or turn over a new leaf, except through magic. So someone wasn’t going to have a life changing experience and jump from Chaotic Evil to Chaotic Neutral or Chaotic Good. Instead, they would usually have this weird progression through neutrality and law.

When alignment shifted radically through magical means, like say, I don’t know, the balance card in the deck of many things, it always felt immensely unsatisfying.

For example, let’s say your Dungeon Master is a bit of a masochist and lets you play evil characters. So you’re playing a lawful evil knight, and you happen to pick up a cursed item that switches your alignment to chaotic good. Congratulations, you now have a completely different character.

The alignment system is used in character creation, both for player characters (the protagonists) and non-player characters or NPCs (the rest of the world). So a character concept always involves the standard nine alignment grid: each character needs to tick one box from each axes to determine how they should be played.

The longer I play TTRPGs, the more problematic this system becomes for me, both as an author who writes characters, and as a TTRPG Games Master -slash- player.

Here’s why it bothers me.

Good and Evil are pretty straightforward. Most people can differentiate between saving orphans and burning down the orphanage while kicking a sick puppy.

Neutral is a little more nuanced and confusing. I’ve often heard it described as self-centered or selfish behaviour, but that definition seems to tilt towards evil. Neutral is also described as seeking balance, or known as the druid alignment.

The differences between neutral and evil can get philosophically murky. Particularly when neutral is defined as unaligned, or just staying out of it. If denying someone help causes considerable harm, then is a neutral action actually evil?

What if you’re denying help to the people trying to stop the big bad? That might have realmwide consequences.

Again, if we follow the argument that neutral alignment is all about balance, we could argue that someone like Thanos is neutrally aligned. Lawful neutral, I suspect. The man has very specific ideas about how things should be done, his own (twisted) sense of fairness, and is terrifyingly preoccupied with restoring balance.

I doubt the Marvel heroes would agree with that analysis. And to be fair, this is a topic that has been hotly debated in nerd communities since the Infinity Wars came out.

These discussions are spurred on by the existence of games like Undertale, which makes you feel like an absolute heel for assuming you’re the good guy out fighting monsters. Undertale paved the way for more discussion around good and evil in games. It suggested that deciding whether something is Good, Evil, or Neutral, tends to depend a lot on where you’re standing.

D&D alignments have also developed their own stereotypes. Lawful Evil is often described as lawful business, or cutthroat means-to-an-ends behaviour.

Lawful good is often lawful stupid; putting yourself in harm's way just because you have an obsessive compulsion to follow the laws to the letter.

And the chaotic alignments are basically outcome based chaos monkeys. Are you a chaos monkey that begets social benefit (chaotic good), or social harm (chaotic evil)? Or do you balance good and evil acts with a degree of deference and unpredictability (chaotic neutral)?

The alignments also create problems when it comes to organic character arcs. Over reliance on alignment makes it easy to write yourself into a corner.

Consider for a moment, your bog standard lawful good paladin.

Since the alignment system originated with Lawful Good as the ‘highest’, most double plus good alignment, what does that mean for characters?

In a literal sense, every character should be working towards a lawful good ideal. That’s boring.

What’s that you say? You don’t need to view character growth from a moral perspective? Oh, but in this case, we do. That’s kind of the whole point of the alignment system, and one of the reasons it’s so limiting. Alignment puts a moral lens on character growth. We’re going to avoid getting lost in the weeds on the specifics of what it really means to be lawful good. This post would be way out of scope if we started to get into how we culturally construct morality.

We will discuss what lawful good (LG) implies in terms of character arcs: the character starts out as morally superior to their compatriots (a bit odd for a new adventurer - not much experience to show for all that pre-adventure growth).

A LG character arc has limited and pre-determined options. Namely, the LG character must either maintain their awful-goodness in the face of certain death.

Or, they risk succumbing to moral relativism and ‘downgrading’ their LG alignment to neutral or chaotic good.**

(*Edit - I’ve been reminded that this depends a lot on your games master - you could fall to neutral or evil, or go in reverse upwards and avoid things changing on the law/chaos axis. I’ve had DMs who treated it more as nine steps up and down than two independent axes, and although the system lends itself to that interpretation, it probably is not the rules as written one).

In older editions of D&D, this could meant losing certain gameplay bonuses, such as their connection to their god.

But to survive, the LG character must realize that sometimes they must act outside of their alignment, recognize that some rules are good and others are bad, and understand when following them is mortally or morally dangerous.

I also find it a bit weird (and very Western philosophically) that lawful good is the ‘highest’ step on the moral scale, when it’s so easy to follow rules directly into creating suffering. After all, history shows pretty clearly that rigid obedience to authority and law can create an awful lot of harm. Controversial Milgram experiments? I’m looking at you.

There’s nothing wrong with a rigidity → flexibility character arc or an

acting with blind obedience → taking responsibility for making tough choices arc.

IF those are the themes that you want to explore. But it can feel like the ONLY feasible arc for a lawful good character, so it’s no wonder that most players don’t want to play lawful good characters, or that this alignment is often considered insufferable to other players at the table.

In the words of my husband, Nicholas, nobody wants Superman to show up and say “You can’t do that,” when everyone else is pretending to be X-Men.

After playing TTRPGs for over 22 years, I’ve seen the alignment system used to prop up lazy stereotypes and write character arcs into a corner more often than I’ve seen it function as ‘useful character shorthand’.

In reality, players are going to do what players are going to do, and nobody, and I do mean nobody, plays their actual alignment ‘perfectly’.

Player alignment versus how they play their characters:

D&D seems to recognize that alignment has its flaws, and recent editions have moved further away from tying alignment tightly to game mechanics.

But, could alignment be a useful tool for Game Masters (GMs), who need to create lots of NPCs on the fly?

Well, yes and no.

Yes, as a very basic answer to the question, “how is this NPC behaving today?”

No, if it’s relied upon too heavily, as it creates a world of cardboard cutouts.

Relying on alignment creates the Oblivion problem: a game where hundreds of NPCs sounds like a handful of people are voicing them. For players, that feels like interacting with stock characters with stilted dialogue. The NPCs all look and sound similar, even the important ones.

Writing your one-off shopkeeper as chaotic neutral or neutral evil as shorthand to show they’re willing to undercut or rob your players, is not the end of the world. It becomes an issue when antagonists rely too heavily on the alignment system to manufacture their personality. Since alignment only represents an in-the-moment measurement of behaviour, they lack depth.

Yes, it’s true that alignment is designed as a morality scale, but behaviour is what it actually measures.

Alignment gives no motive. People change, and situations change people. If alignment doesn’t really hold up to real people, how can it create immersive, real-feeling characters?

For instance, I may be lawful good when it’s my daughter’s bedtime. I’m sure from her perspective in the moment, I’m lawful evil, or lawful stupid. But I’m the first to admit that I am chaotic neutral (at best) before my morning caffeine.

Alignment should be little more than a starting point to represent how the character is behaving at a particular moment in time.

The alignment system may be used to justify a character’s behaviour, but it never really gets at the deeper “why”. It’s a measurement of surface behaviour, not motive.

I have seen so many groups get absolutely lost in the reeds over alignment questions and nature/nurture questions. Did a character start evil? Have they ever been healthy? Should the lawful good paladin be cool with their ragtag murder hobo team killing orphaned kids who got flagged on a routine detect evil?

Oh yeah, in D&D, creatures are either evil or not evil. On that note, alignment has a problematic history of being tied to character race. Um yeah. There are entirely evil races in Dungeons and Dragons.

Evil races, in my roleplaying game? More likely than you think.

We also miss out on the nuanced stories we can tell by looking at characters, even antagonists, through different lenses, such as levels of health.

No one is perfectly good or perfectly evil all of the time.

So what can we do instead?

There are better systems for creating real feeling characters in TTRPGs and for writing in fiction in general.

First of all, D&D is not the only TTRPG. There are oodles of options out there, some of which I’m discussing in an upcoming video with serial GM and librarian Sam Elkind, who takes us through some of his collection.

There are also systems based on D&D that are moving from alignment. One of the bigger options for fantasy gaming is Pathfinder, by Paizo. Paizo continues to sprint away from its D&D roots and Pathfinder has done away with the alignment system, in its newest edition. It mechanically makes a lot of sense. I may write more on this, but for the nerdier among you, there’s a great video by The Rules Lawyer. Ronald explains it way better than I could.

And if you’re married to the Dungeons and Dragons franchise, well…

Hasbro has made a lot of anti-consumeristic moves recently, so I’m moving away from it, but there are other systems that are just as quick shorthand for D&D, and that can provide much deeper characterization.

For example, the Enneagram, which, by pure coincidence also has 9 categories. The Enneagram is all about core fears and desires, which makes it much more useful system for developing deep, real-feeling characters - even on the fly.

it gets at the carrot and the stick, which makes for more compelling characters.

Someone who craves control is going to behave differently than someone who craves justice, or personal significance, or attention. And they may float up and down in levels of health, depending on their level of stress and behave differently, like, you know, real people do.

I’ll be doing a series on this topic, but here are a couple of examples to get your brain started.

How would an Enneagram Type 9 villain (who craved peace at all costs) behave? They might sometimes act in chaotic ways, or act within the law to get their need for peace met. They might sometimes do things that ended up being for the greater good on purpose or by accident. They would also absolutely throw innocent people under the bus to maintain the peace in the group. Villain, remember?

But using any enneagram lens and thinking of behaviour as a spectrum of health may be more nuanced and interesting, and allow your players to explore different themes. And you can still have them fight the old chaotic evil cult leader who sacrifices babies to elder gods. You know, as a treat.

Anyway, you see enough of these 9x9 alignment grids, and you start to go a little insane.